The Artificial Law Clerk

Artificial intelligence for the practice of law is finally here with the “Artificial Law Clerk”. You can now radically accelerate your research process by having the Artificial Law Clerk review your legal search results.

Artificial Intelligence for Law

In our first commercial offering, computers can read with comprehension and reason about what they have read.

With Perftech.ai technology, legal professionals can have an computer law clerk (“the Artificial Law Clerk”) review caselaw to filter search results for their relevance to a specific case and even a specific hypothesis within a case.

Furthermore, as we continue development, Perftech.ai for Law will increasingly be able to outline and write opinions automatically.

How is this possible? The leading computer-based methods to analyze English have relied on associations and pattern-matching and have given the world technology that can guess at the positive or negative sentiment of text — and which, more recently, can generate semi-realistic original articles in English.

But these methods, ultimately, are still merely guessing based on patterns in order to produce their results. There is no meaningful sense in which these AI tools understand the text that they read and write.

Our technology, developed over several years, takes a radical leap forward by going beyond pattern-matching with true knowledge of the English language. In AI parlance, we have augmented machine learning techniques with our in-house natural language processing. The PerfTech.AI system has the ability to extract facts and opinions from documents and to manipulate these ideas into logical arguments.

The Artificial Law Clerk Accelerates Legal Research

The first and primary application of the Artificial Law Clerk is to make it faster for humans to review legal search results for relevance to a specific case.

The Problem:

- Legal searches produce an overabundance of search results;

- These results require costly human review;

- Better keyword searches don’t fix the issue;

- Review is difficult to automate, because it uses common-sense and legal knowledge

The Solution:

- The Artificial Law Clerk uses legal knowledge and common sense to review search results;

- The human legal professional can specify additional guidance (in English);

- The most useful search results “float to the top”;

- Automatic review can be run overnight;

- The bottom line: reduced cost and time, with better results

The Problem: "Overabundance" of Legal Search Results

Legal professionals tell us that when they turn to a legal search engine for case law that is relevant to a particular client engagement, they generally receive an overabundance of search results. This happens because the body of case law is so vast and because, typically, many cases will match a particular set of search keywords.

The “overabundance” of search results creates two challenges. First, it means that reviewing legal search results can be slow and costly. If, say, it takes a human 10 minutes to review a single search result for relevance to a particular client engagement, then the task of reviewing search results easily stretches into hours of human time. Second, the overabundance of results means that critical search results may be lost. Due to the time it takes to review search results, there may be a search result that would be critically useful to a particular client engagement which is overlooked and never used, because it was listed in the search results but not quite at the top and it did not fall within the results that you had time to review. In short, you risk missing out on critical search results.

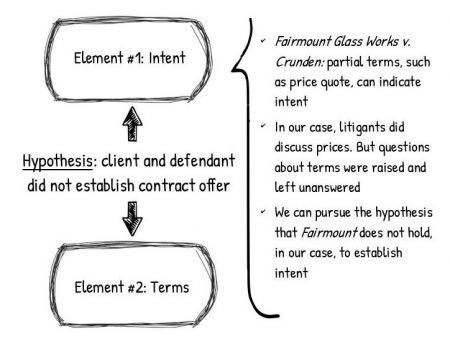

Example: Discussion of Terms in a Contract Offer

Let’s consider an example about a hypothetical situation involving the formation of a contract. (Some of the legal details here may be simplified or not phrased inaccurately; we are not legal experts and do not pretend to be, as we’ll discuss more below.) We’ll use this example to illustrate the Overabundance Problem in legal search results.

Suppose that your practice has been retained by a Client concerning the alleged violation by that client of a contract, and you (or your firm or colleague — we’ll just say “you”) are now working and searching cases on behalf of your client. Suppose further that you are exploring the possibility that the contract could not have been violated because it had never been formed.

Your thinking about the case might be captured roughly by the accompanying Figure 1. You might obtain a favorable outcome for your client by showing that intent had not been established and thus that the contract offer had not been established. A discussion of partial terms can establish sufficient “intent” for a contract offer in some cases, per Fairmount Glass Works v. Crunden, but in some cases partial terms having been discussed is not sufficient. A search of the case law might turn up legal opinions that are favorable or disfavorable to your client’s argument because they involve situations in which partial terms were discussed but the intent to form a contract was judged to have been absent.

With this objective in mind, you conduct a legal search for similar and relevant judicial opinions. You try searching using different combinations of keywords, such as “contract AND offer”, possibly “contract AND offer AND terms”, and so forth. The search engine does its job in delivering documents that match the keywords, but not all of the opinions are relevant to your purposes. Though they all involve the terms of a contract, they don’t all involve whether terms of the contract had been established, which is in fact the aspect of these cases with which you are concerned.

Although the search results match all of the keywords you have supplied, they don’t all match your personal criteria, because some of your criteria cannot be captured efficiently by keywords. We can illustrate (again, hypothetically), with the following table:

| Discoverable Language | Non-Discoverable Language | |

|---|---|---|

| Search Result #1 | “contract offer” “intent” “terms” | “‘…the timeline for receiving the building materials, however, was not nailed down,’ in the words of Smith.” |

| Search Result #2 | “offer for a contract” “intent” “each term” | N/A (not a useful search result) |

| Search Result #3 | “contract” “terms of the offer” | “However, regarding the zoological sideshow, there was still the matter of the emus.” |

The three imaginary search results shown in the table above have language in common that is easy to search for (shown in the middle column) and differing language that is difficult to search for (shown in the right column). The first and third search results have details within that are relevant to your search, and the second doesn’t.

Each search result has language is that is discoverable by keywords and language that is not. Some “undiscoverable” language in legal search results is critical to your work. That’s why, generally, not all search results match the legal professional’s objective — and that’s why legal search tends to produce an overabundance of search results.

Because of Overabundance, Humans Must Review Search Results

In the table of imaginary search results above, we can observe that the key passages excerpted in the right column would be difficult or impossible to find using keywords. For example, it would be unsuccessful to find Search Result #1 by adding keywords as “discussed”, “unresolved”, or “partial”, because these terms are not present in the key text. Even if the search engine uses synonyms for your keywords, synonyms will capture only a portion of relevant language and miss other language, such as “nailed down” in Search Result #1. The situation is even more extreme in Search Result #3. The sentence, “However, regarding the zoological sideshow, there was still the matter of the emus” quite possibly referred to contract terms that had not been established.

It is true that trying different search terms can help find accurate results — but only to a point. Without review of search results, key details can be lost. In this hypothetical example, you might try searching for “contract AND offer”, possibly “contact AND offer AND terms”, and so forth. The challenge is that, in the search results the terms “contract” and “offer” can be expected to appear, but there are an infinity of possible “terms” that can be raised and left unanswered in a contract situation. For example, a property owner might discuss construction company or general contractor what types of building materials will be used, whether one part can be substituted for another, what role subcontractors might play in the work… the list goes on. The more that a case dives into particulars, often critical details, the less standard are the terms and language used. As a result, these details tend to be impossible to find through keyword search alone. Some judicial opinions of interest to your client’s situation might happen to use the exact words “terms”, “discussed”, “unresolved”, but most will not.

The solution, to date, has been for the human legal practitioner to review the search results one by one. This is where the Artificial Law Clerk works its magic — by conducting the review for you.

The Artificial Law Clerk Reviews Your Search Results

We have just discussed how researching with a legal search engine tends to produce a time-consuming overabundance of search results. We discussed how this overabundance is caused by the fact that opinions generally have important language that is not discoverable by keyword search, because that language is nonstandard and relates to the fact pattern of each case, rather than to standard legal jargon. Finally, we observed that the remedy for this problem, until the present time, has been for humans to read and review these opinions.

This brings us to the question of the Artificial Law Clerk — what it can do and how it works. We will show how the Artificial Law Clerk can review search results, with massive savings of time and expense.

Analyzing “non-discoverable” (or “non-keyword”) language

As we have discussed, language that does not consist of standard legal keywords and hence which is not “discoverable” by search engines generally requires human review. The Artificial Law Clerk steps in right at this point of difficulty by analyzing this language.

Let’s return to the example above about contract intent, and look at how the Artificial Law Clerk can process the language:

Search Result #1, in our imaginary example, contained the language: “‘…the timeline for receiving the building materials, however, was not nailed down,’ in the words of Smith.” Our artificial intelligence comprehends this sentence in a way that is analogous to a human’s approach. First, it notes that the sentence is in the passive voice, and that the main verb is “nailed down”. It notes that the object of the “nailing down” is the “timeline”. It knows that one possible meaning of “nail down” is to “hammer nails through”, and another is to “finalize”. But it knows that the concept of hammering nails through a timeline doesn’t make sense, and it concludes that this sentence discusses something had not been finalized. Even without going into further detail, the artificial intelligence has picked up that this case quite possibly involves the terms of a contract that have been discussed but not agreed upon.

In Search Result #3, the Artificial Law Clerk can use a similar thought process to flag the sentence, “However, regarding the zoological sideshow, there was still the matter of the emus.” Based on the words “still” and “matter”, the engine concludes tentatively that a contract term has been left unresolved. Furthermore, since an emu is a type of animal, and since the engine knows from the document that the contract concerns a “zoological sideshow”, the engine concludes that the emus represent a detail in the performance of the contract in that case.

As you can see, Artificial Law Clerk conducts automatic analysis by combining some knowledge of grammar, the meaning of English words, and the prompt that it has been supplied by the legal professional. To do its work it needs to know, in this case, at least a little bit of what a “contract” is. So that brings us to the question: does it know the law, and how could such a thing be possible?

Does this Artificial Intelligence Know the Law?

Our system uses a combination of accumulated knowledge and user-supplied knowledge. How does the Artificial Law Clerk know the law? When we discussed the contract example just above, we assumed that the Artificial Law Clerk had a basic understanding of some key elements of U.S. contract law. For example, the artificial intelligence knew that establishing intent is a defining element of a contract offer. Furthermore, it knew that discussing prices amounted to discussing partial terms, and that partial terms can sometimes but not always establish intent. And so on… How does the Artificial Law Clerk know about the law?

The short answer is that it doesn’t. Our system has been designed to work without knowing the law, although it will retain some legal lessons through its use and attempt to make useful suggestions.

You might say that the Artificial Law Clerk is like an “astute layperson”:

- It can evaluate a question or a hypothesis relative to a document, using common knowledge and common-sense logic;

- It cannot understand all statues, nor will it typically know anything about legal rules that have become standard practice but which are not explicitly mentioned in an opinion;

- It does not currently know how to weight possibly conflicting legal rules etc from different sources;

- It can remember legal rules expressed in simple English and apply them to other cases in the future.

Our system has been designed to work without expertise in a particular legal area. It retains legal principles that it encounters and thus can work more efficiently over time, but it is designed to be able to fill gaps in its knowledge by analyzing the search results you have pulled up and also by interacting with you or the legal professional who is in the process of using it.

Analyzing a Fact Pattern

To enable the analysis of legal fact patterns, we have equipped Perftech.ai for Law with common sense, which has proved notoriously elusive for state-of-the-art artificial intellience.

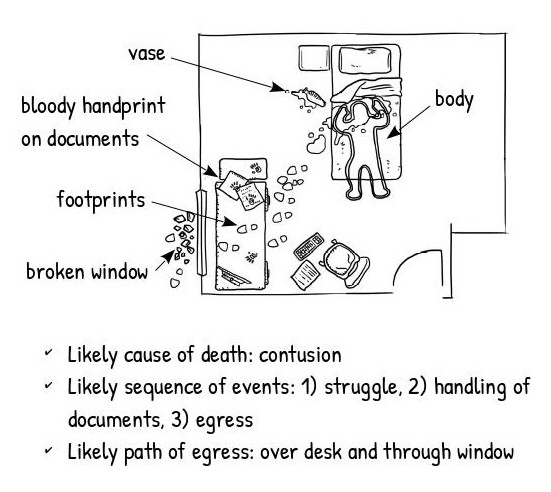

For example, consider an automated analysis of a fact pattern about a crime scene, pictured here. When reviewing an opinion or legal documents, a human might draw a sketch like this to represent the various pieces of evidence and how they fit together. The sketch aids the human in drawing conclusions about the situation. The Artificial Law Clerk does not draw any sketches or look at images, but it thinks in a similar way to make conjectures about a fact pattern.

Above, in our contract example, we discussed how understanding English enables the Artificial Law Clerk to identify important language that is undiscoverable by keywords. This is possible by understanding real-life situations, as opposed to legal terminology and legal reasoning. In other words, our computer engine can process and understand the “fact pattern” of a case.

Imagine a legal document that describes the evidence found at a crime scene. The Artificial Law Clerk is reading this document. (The engine is not looking at any images and does not have any ability to analyze images; the figure is presented here for illustrative purposes only.) While reading the document, the artificial intelligence draws conclusions and potential conclusions in English.

This process of drawing conclusions can be portrayed schematically as a kind of formula:

fact about situation + common sense = conclusion(s) about situation

When the engine reads a specific fact about the situation, such as the crime scene above, it combines the fact with relevant general knowledge in order to draw conclusions about the situation. For example, when it reads that, at the hypothetical crime scene, paper documents were found with “bloody handprints” on them, it draws the conclusion, among others, that the documents were handled.

More examples of this formula works, given the crime scene above, are shown in the table below:

| Fact about Situation | Common Sense | Conclusion(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Footprints were found on the desk near the broken window and outside the window. | Footprints indicate the direction in which a person has walked. | Someone may have walked to and through the window. |

| A vase was found nearby. | You can use blunt object, such as a vase, to strike someone. | A blow from the vase might have been the cause of death. |

| A vase was broken on the floor. | A vase is fragile and can break easily. | The vase might have been broken accidentally. |

Whether this common-sense reasoning in the table above strikes you as primitive or as advanced, remarkable or unremarkable in itself, the point here is that it is a key driver of the review of search results that we have described above. This is the kind of reasoning that enables the Artificial Law Clerk to review search results for you. It works because the Artificial Law Clerk can make sense of the “non-discoverable” terms in search results, as we have described above. This reasoning, you might say, is how the Artificial Law Clerk, when reading the hypothetical Search Result #3 above, can conclude that the emus in the zoological sideshow might represent a contract term that has been discussed but not resolved. This is a taste, in short, of how the technology of the Artificial Law Clerk is unique and how it makes the job possible.

Let Your Best Results Rise to the Top

As the Artificial Law Clerk reviews the results of your legal search, it reorders the results. The more relevant results are promoted, and the less relevant results are demoted. As a result, the most useful results “float to the top”. Your work is smoother, more efficient, and more informed. You can obtain better and faster legal results, increasing client satisfaction and optimizing your billable outcomes and/or case load according to the goals of your organization.

The way that useful search results “rise to the top” can be a metaphor for your legal organization’s results. With a smart approach, working with artificial intelligence, you can let your best results rise to the top.

Use Case: Running the Artificial Law Clerk Overnight

Let’s imagine a day in the life of using the new Artificial Law Clerk… It might be as simple as running your searches overnight. That is, at the end of a day of work, your team members conduct their legal searches, possibly trying a few different keywords. Then, rather than laboriously review the results, you all go home for the day (or, maybe more likely, work on something else). In the morning, the search results have been sorted for relevance by the artificial intelligence.

Often in life, doing something faster means doing it worse, but in this case, the opposite is true… If you are able to review search results more quickly, your billable time goes down and you can get more accurate results, including that key search result that might otherwise have been missing. Reviewing search results faster enables the practitioners of legal services to perform more competitively in both cost and quality.

- In a typical use case, a legal professional performs a typical keyword-based search, provides some questions to the Artificial Law Clerk, and leaves it to review the search results overnight. In the morning, the search results have been sorted by relevance with explanatory annotations of each opinion;

- The automated review of search results not only reduces cost, but improves legal results, by putting more highly relevant search results at the top of the queue for the legal professional

Getting Started

We are coaxing the Artificial Law Clerk onto the public stage. We are moving at an intentional pace because the potential of the technology is great and we want to make sure that the delivery is successful.

Our hope is to make the technology widely available to the practitioners of law and legal services, through a small number of institutional partners. Working with a couple of big partners should enable us to focus our ongoing research & development on the unique aspects of our technology, to avoid “reinventing the wheel” in building our own legal search engine, and to enter a symbiotic relationship with a major player in the field, to the benefit of both parties and the industry as a whole.

In concrete terms, this means that we will not focus on issuing press releases, engaging in hype about artificial intelligence, or publishing carefully curated demos of our technology. Rather, our goal is to connect with the right partner or partners, show and share more, and begin to implement technology together with an eye toward a big future.

If you are interested, let’s talk. We will be happy to divulge more details about our technology. We would love to hear more about the needs of legal practitioners and how the Artificial Law Clerk can solve problems. We are ready to listen and we are ready to get down to business.